The career of Major-General Sir Denis Pack, spanning some three decades from the 1790s to early 1820s, seems to strain plausibility. Even before his participation at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, he was honored for his bravery and leadership at Roliça/Vimiero, la Coruna, Bussaco, Ciudad Rodrigo, Salamanca, Vittoria, Pyrénées, Nivelle, Nive, Orthez and Toulouse. With the exception of Talavera, he fought in every significant battle of the age, and was second only to Wellington in terms of battle honors bestowed.

He also experienced the tribulations of a soldier’s life, being captured twice, wounded approximately eight times, and recovered from Walcheren fever, no mean feat in the context of Georgian medical knowledge. In addition to participating in some of Britain’s most celebrated military victories, he also witnessed some of their failures, particularly those at Walcheren. Furthermore, he was present at many of the most significant social events of the early nineteenth century, including the Duchess of Richmond’s eve of Waterloo ball and the coronation of George IV in 1821.

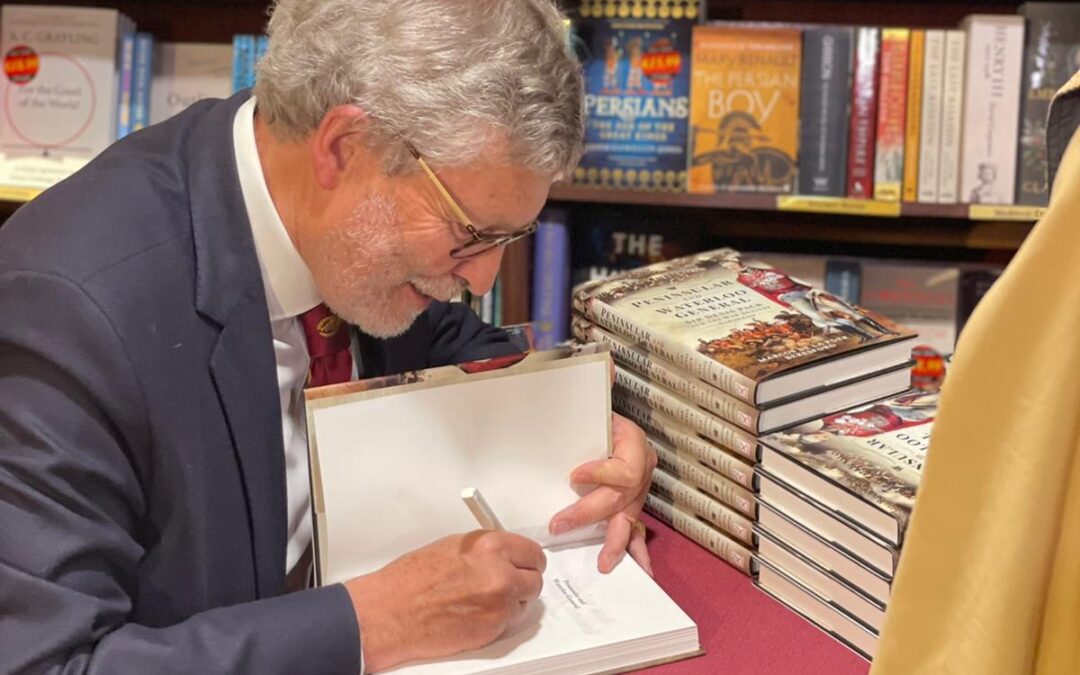

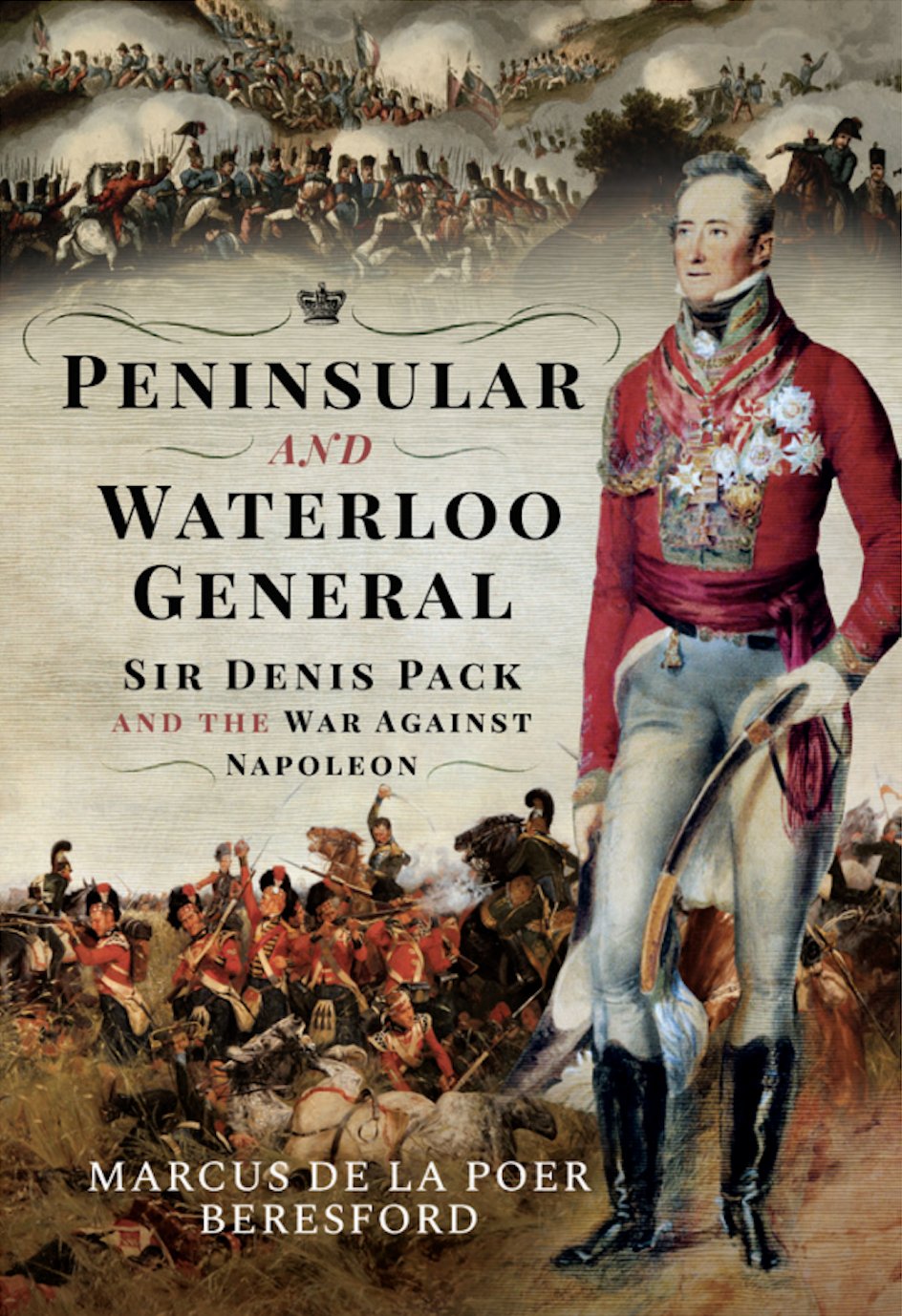

After a long and distinguished legal career, the author Marcus de la Poer Beresford has turned his attention to Napoleonic history, particularly the contribution made by Irish soldiers to the series of conflicts that constituted the war against Napoleon. In addition to numerous scholarly articles, his 2019 monograph on the life of Marshal William Carr Beresford—an ancestor—was well-received for the quality of research it demonstrated, suggesting that de la Poer Beresford’s legal training has been well employed in his forensic investigations into the past.

It is therefore unsurprising that the work is logically laid out, with Pack’s career explored systematically and comprehensively. Illustrated lavishly with twenty-nine plates, primarily in color, the work is further enhanced by eighteen battlefield maps, which substitute ably for extensive narratives of the battles they represent. A short opening paragraph in each chapter deftly situates the reader into the action to follow, and while the author indulges in some general discussion of the context of each phase of Pack’s career, Pack is kept firmly in sight.

Furthermore, while the overall tone of the text is that of relatively conventional military history writing, it makes a slight nod to the current trend for “a flight to the suburbs,” which sees military historians focus on the impact of war on society and its effects on non-combatants. This is evident in a description of Pack’s servant giving birth to a child on campaign, segueing into a moving description of the hardships upon women and children caught up in the conflict.

In the work’s foreword, Rory Muir notes that Pack’s early death in 1823 may be one of the reasons why, unlike so many of his contemporaries, he did not produce any memoirs. Furthermore, Pack’s footprint in the historiographical record may be light simply because for much of his career in the Peninsular War he commanded Portuguese troops, the records of which are often under-utilized by English-speaking military historians. The author points to a 1945 article in Blackwood’s Magazine, which was apparently based upon a journal belonging to Denis Pack which has not survived to the present day. This misfortune has its compensations, causing the author to consult not only obvious sources such as the correspondence of Wellington, but more obscure archival records such as those of the Portuguese military.

He also exploits to the fullest degree contemporaneous accounts of the Peninsular War written by six men from Pack’s regiment, which greatly augments our depth of knowledge. Four of these accounts were written by enlisted men, allowing the author to consider Pack’s career from an often-absent viewpoint. Furthermore, such accounts are supplemented by similar memoirs written from other participating regiments, particularly those of the 42nd regiment (the Black Watch).

From such sources, the author reconstructs an impressive career that emerged from an unimpressive start. Born in Ireland to a family descended from seventeenth century Northamptonshire settlers, Pack enjoyed social respectability as the only son of the dean of Ossary, attending Kilkenny College and for a time, Trinity College. At sixteen he was commissioned as a cornet in the 14th Light Dragoons, but was court martialed for striking another officer. While his precise punishment for this offence is unclear, he reappeared two years later as a “gentlemen volunteer,” serving in Flanders as part of a disastrous wintertime campaign commanded by the Earl of Moira.

In 1795 he became a lieutenant by purchase, formally beginning a career dominated by his exploits in the 71st regiment as well as a stint commanding Portuguese troops allied to Britain against Napoleon. The work depicts a brave yet humane individual, who demonstrated a high degree of concern for the men under his command, despite his reputation for occasional irritability.

The key strength of this work lies not only in the excellence of its research into the life of Denis Pack, but its ability to utilize Pack as a prism through which to understand the lived reality of army life in the early nineteenth century. This is particularly true of its exploration of military officers’ personal finances, careers and the complexities of the purchase system, which saw appointments and promotions achieved through a mixture of merit, purchase and canvassing.

Although considered a gentleman, Pack enjoyed neither powerful familial connections nor a large private income. This consideration, the author argues, might explain why he transferred from a cavalry to an infantry regiment, allowing him to purchase a cheaper commission and also ensuring that he was placed to distinguish himself. Financial considerations also caused Pack to turn down at least two appointments, including a prestigious posting to the West Indies and the position of Quartermaster-General to the cavalry.

This work also serves to explore what life was like for officers on campaign, discussing quotidian aspects of military service such as discipline, provisioning, living standards and leave patterns. Readers whose understanding of this period comes from historical fiction may be surprised to learn that officers in the field were often obliged to accept the same privations as enlisted men, with food shortages and poor-quality accommodation a frequent occurrence for officers and men alike. There is also a fascinating discussion of Wellington’s disapproval of officers taking leave to attend to business which in many cases, consisted of going to London to lobby for promotion which, Wellington argued, ought to be earned by service in the field.

Although not extensively discussed, the work also alludes to the cultural, logistical and operational difficulties of the British Army’s military collaboration with the Portuguese, a reality of multinational war that remains unchanged to the present day. This is reflected in Pack’s dismissal of Portuguese troops’ courage, which he claimed “is of a vastly changeable nature,” suggesting a level of distrust and disdain which was not borne out by their performance in the battlefield, nor by Pack’s own official reports. It is to be hoped that an increased engagement of Anglophone historians with Portuguese—and Spanish—archival sources will allow for greater understanding of these tensions.

Moreover, in addition to reminding us that Britain was far from the only nation that stood against Napoleon, it also presents the resulting conflict as a global war, which engulfed Europe and parts of Africa and South America, as evidenced by Britain’s 1805 attempt to retake the Cape Colony from the Batavian Republic, a vassal state to Napoleonic France. Furthermore, it illustrates that alongside the glorious victories of the Peninsular campaign and Waterloo there were disasters, particularly in the Low Countries. This serves to remind us that the wars against Napoleon were piecemeal, complex and varied in nature and character, with a battle space that presented new and ever-changing challenges to military commanders like Pack.

By its very nature, this work is not an exhaustive account of the wars against Napoleon, and the author has quite correctly decided against extensive analysis of the singular political and cultural conditions that created Napoleon, Wellington, Pack and the host of other colorful characters which inhabit his research. This decision is sensible, allowing for focus on Pack at all times.

What is less successful is the lack of detail regarding Pack’s relationship with Ireland. In the absence of a personal memoir this is probably unavoidable, as Pack becomes difficult to trace via other people’s correspondence when he is not on active service or in London. Occasional traces of his life in Ireland are evident; he participated in the court martial of Mathew Tone after the 1798 rebellion and was awarded the freedoms of Kilkenny, Cork and Waterford during his lifetime. Moreover, the installation of a memorial bust of Pack at Kilkenny Cathedral in 1829 was a significant event, with a procession of Waterloo veterans through the city.

This suggests that Pack’s relationship with his Irish origins, and of the legacy he left behind was a complex one. Marcus de la Poer Beresford’s work constitutes an excellent first step in assessing such a legacy, and in bringing to life a world that is both modern and remote, where merit and accidents of birth determined in equal measure a person’s worth and impact upon the wider world.

— Laura Brown, Centre for Military History and Strategic Studies, Maynooth University

This review was published in the Irish Literary Supplement Volume 42, No.1 (Fall 2022)